China’s One Belt One Road Will Open Trade Routes and Raise Barriers to U.S. Law

On May 14, 2017, President Xi Jinping of China outlined plans to fund China’s One Belt, One Road (OBOR) initiative. If successful, OBOR would alter the global trade landscape and, secondarily, likely curtail the global reach of U.S. law. The potential legal effects of the OBOR and other non-U.S. dollar- and Bretton Woods system-centric trade and finance initiatives were discussed in an earlier MassPoint Occasional Note. Given President Xi’s fresh announcement of concrete plans to carry forward the OBOR project, MassPoint’s earlier discussion of the project’s potential curtailment of the global reach of U.S. law– and the links between U.S. dollar and financial system strength and the global reach of U.S. law– is revisited here. For a more detailed and technical legal analysis of U.S. dollar and financial system-tied jurisdiction, contact the author, Hdeel Abdelhady, at habdelhady@masspointpllc.com.

One Belt, One Road: “Project of the Century”

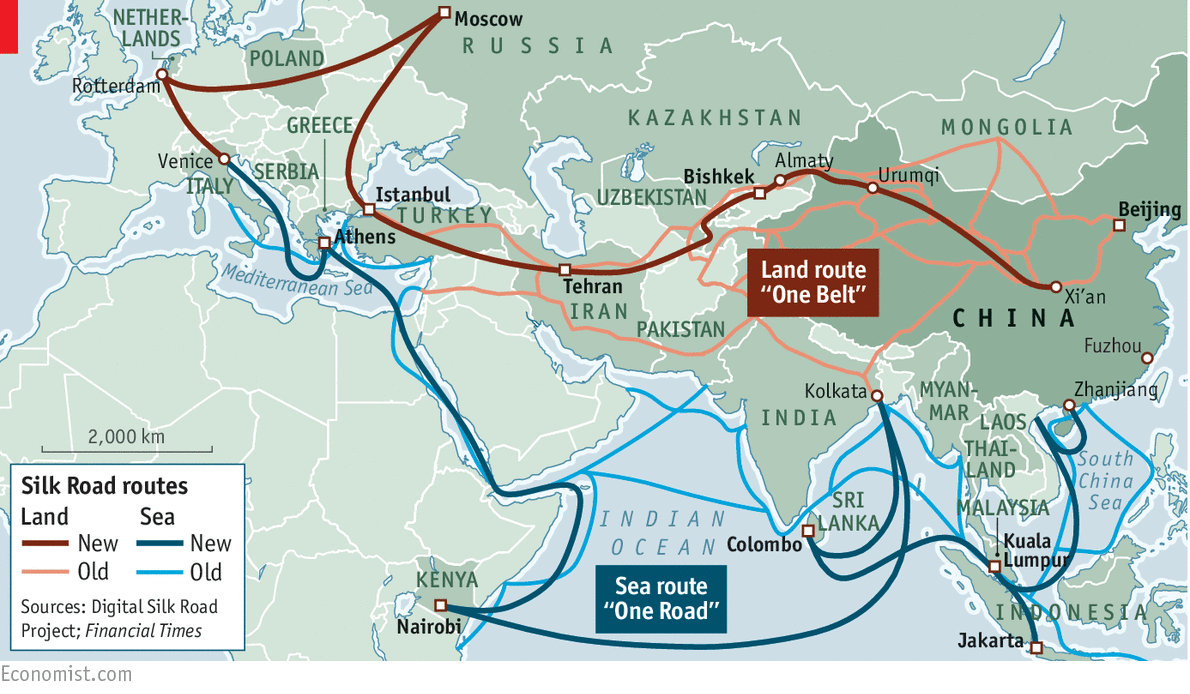

President Xi Jinping on Sunday detailed plans to fund China’s One Belt, One Road project (OBOR), an expansive trade and infrastructure initiative that aims to connect by land and sea over 60 countries in Asia, Europe, the Middle East and Africa and produce over $21 billion in economic activity. At the opening of the Belt and Road Forum in Beijing on Sunday, President Xi described OBOR as “this project of the century.” Ambitious and expansive, OBOR, as the New York Times put it, “looms on a scope and scale with little precedent in modern history, promising more than $1 trillion in infrastructure.”

One Belt, One Road Funding; Renminbi Internationalization

According to the Times, China has to date spent $50 billion on the OBOR initiative, which was announced in 2013. On Sunday, President Xi announced that China would increase OBOR funds available to Chinese state banks and funding facilities, including that the China Development Bank and Export Import Bank “would dispense loans of $55 billion between them, and the Silk Road Fund would receive an additional $14 billion.” “About $50 billion more would be directed at encouraging financial institutions to expand their overseas renminbi fund businesses.” The latter prong of the OBOR funding plan would bolster efforts to internationalize the renminbi, an effort that has realized relatively modest but appreciable gains in recent years—the IMF added the renminbi to the Special Drawing Rights (SDR) basket of currencies in October 2016 and the currency has gained as an international payments currency (albeit with a decline in 2016 from 2015 attributable to U.S. dollar strength and capital controls, see SWIFT’s RMB Tracker and a Financial Times discussion of the renminbi’s “retreat” in 2016).

One Belt, One Road Would Alter Global Trade and Curb the Global Reach of U.S. Law

The OBOR, even if partially successful, would, as many analysts and commentators have noted, alter the global trade landscape, if not “shake up” the global economic order in place since the end of World War II. Less discussed (except, for example, in this 2015 MassPoint Occasional Note) is one likely secondary effect of the OBOR and other trade and finance initiatives that are not centered on the U.S. dollar or the Bretton Woods system: the likely curtailment of the global reach of U.S. law.

U.S. Dollar and Financial System Strength Facilitates Extraterritorial Reach of U.S. Law

American economic and financial heft facilitates the extraterritorial reach of U.S. law.[1] For example, global transactions that on their face appear disconnected from the United States but are denominated in U.S. dollars and processed through the U.S. financial system “touch” the United States, and therefore come within its jurisdiction and create a jurisdictional nexus between the United States and foreign parties, property and events associated with those transactions.

Global Reach of U.S. Economic Sanctions Laws and Regulations: European Banks Cases

Between 2009 and 2015, eight European banks—including HSBC, BNP Paribas, Standard Chartered, and Credit Suisse—were assessed combined U.S. imposed penalties of over $14 billion for, among other offenses, violating various U.S. sanctions programs, including against Cuba, Iran, Sudan, Libya, Myanmar and certain “blocked” parties associated with sanctioned countries, terrorism, weapons of mass destruction proliferation, and narcotics trafficking.

Many of the transactions that led to U.S. sanctions liability involved U.S. dollar payments on behalf of foreign parties in relation to foreign business– the nexus to the United States was not apparent in many cases. For example, according to U.S. authorities, a BNP Paribas branch in Paris maintained an account for UAE company that was part of an energy group ultimately owned by an Iranian citizen and resident. The same Iranian individual beneficially owned the Paris bank account, through which the UAE company received payments from its sales of “Turkmen liquefied petroleum gas to Iraq.” Related to those sales, BNP Paribas processed, through U.S. banks, about 114 transactions worth $415 million. To evade U.S. sanctions, the bank concealed in its payment messages to U.S. banks the links between the UAE company and Iran. The transactions violated U.S. sanctions because the benefits of the U.S. dollar transactions processed through U.S. banks were received in Iran.

For these and numerous other violations, BNP Paribas paid an unprecedented $8.9 billion penalty, pled guilty to sanctions-related criminal charges, and had certain of its U.S. dollar clearing privileges suspended for one year. The UK’s Standard Chartered Bank and HSBC paid, respectively, $977 million[2] and $1.9 billion for sanctions, anti-money laundering, and related violations.[3] Germany’s Commerzbank admitted U.S. sanctions and anti-money laundering breaches and agreed to a $1.45 billion penalty.

One Belt, One Road Could Put Significant Trade and Transaction Volumes Beyond the Reach of U.S. Law

Trade and investment between and among emerging and developing jurisdictions have gained in recent years. Such trade and investment flows will likely be reinforced by concerted efforts to develop new commerce channels that, given their pedigree, are detached from the U.S. dollar and financial system. The OBOR, as a significant non-U.S. dollar- and financial system-anchored trade and finance framework, if it materializes, would be the premier facilitator of such trade, finance and investment flows.

NOTES

[1] A distinction should be made between the bases for, and the effects of, U.S. jurisdiction. In the case of the kind of U.S. dollar and financial system-tied jurisdiction discussed here, the basis for U.S. jurisdiction is territorial—transactions processed through the United States financial system “enter” U.S. territory. The effects are extraterritorial, to the extent that parties, property, and/or events outside of the United States are affected or implicated.

[2] Standard Chartered was fined twice. First, in 2012 by federal and New York authorities for sanctions, anti-money laundering and related violations. And second, in 2014, by the New York Department of Financial Services following the regulator’s determination that SCB had failed to remediate anti-money laundering compliance deficiencies identified in the 2012 actions. The 2012 and 2014 penalties total $977 million.

[3] The discussion of cases herein is concerned only with U.S. sanctions enforcement and relevant jurisdictional dimensions (not merits), and not with any anti-money laundering or derivative state law breaches. The enforcement of U.S. unilateral sanctions against non-U.S. parties is particularly controversial, given that unilateral sanctions arguably further U.S. policy objectives, rather than multilaterally agreed policies or the integrity of financial systems. While certainly interesting, these issues are beyond the scope of this publication.

Author Contact Information:

For more information about this publication or related services, please contact Hdeel Abdelhady at habdelhady@masspointpllc.com or +1 202 630 2512.